Every year, scientists stumble upon viruses hiding in the most unexpected corners of the planet — and 2025 was no exception. In the second edition of our New Microbes Discovered in 2025 series, Sarah Wettstadt explores newly discovered viruses from this year, from hypersaline environments to animal hosts and grapevines, expanding our understanding of viral evolution and potential applications. #NewMicrobes

Haven’t read the first edition yet? Read New bacteria identified in 2025

Haloviruses like it hot and salty

Solar salterns are unique ecological niches due to their high salinity and temperature. Within these extreme environments, microbial diversity is low and dominated by haloarchaea and halobacteria, as well as their phages.

The square-shaped Haloquadratum walsbyi is one of the most abundant haloarchaea, yet its phages are currently unknown. Because it harbours a plasmid from the PL6 family with mobile genetic elements, the study “Novel viruses of Haloquadratum walsbyi expand the known archaeal virosphere of hypersaline environments” sampled the solar salterns in Santa Pola, Spain, to search for its haloviruses.

The researchers identified 25 distinct viral genomes and confirmed Haloquadratum walsbyi as their host. Categorised into the three genera “Polavirus”, “Squarevirus”, and “Walsbyivirus”, they fall into the new subfamily “environmental Haloquadratum viruses” within the Haloquadratum family. Like their close relativesin the Haloferuviridae family, they are dsDNA spindle-shaped haloviruses.

Their core genome consists of 20 genes, with the pan-genome coding for 113 proteins. Genera-specific genes are located in the hypervariable region together with several genes with no predicted function. As such, this study broadened the scope of our still-limited understanding of archaeal viruses.

New bacteriophages as potential therapeutic tools

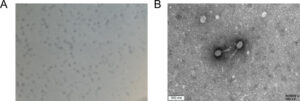

The American cockroach is a potential disease vector. However, the creature is also considered to have potential medicinal value in Chinese medicine. Based on this dual role, the study “Isolation, characterisation, and genomic analysis of a novel phage WSPA with lytic activity against Serratia marcescens” explored the gut microbiome of the animal to find novel bacteriophages against clinically relevant pathogens.

While Serratia marcescens was the most abundant bacterial species, Serratia phage PS2 was the most abundant phage in the viral community. Additionally, the scientists purified and propagated Weishan phage WSPA. They showed that it lysed only Serratia marcescens strains — 14 of the 17 tested — over a temperature range from 4°C to 50°C.

Its linear dsDNA is made of 174 kbp, including six tRNAs and 273 open reading frames (ORFs). Of these, multiple proteins are related to DNA replication, metabolism, and packaging, all likely happening independently. They identified a DNA primase (which overcomes the semi-discontinuous DNA replication) as well as a helicase, ligase, and exonuclease A.

Further, WSPA contains an extensive lysis module, including a lysozyme to degrade bacterial peptidoglycan and a lysis mediator to regulate infection cycle duration and ensure optimal lysis. Based on these early results, WSPA might be a promising therapeutic tool against pathogenic Serratia marcescens.

A new co-viral infection in bass skin lesions

The largemouth bass, endemic to North America, is named after its oversized jaws. Since it is a popular sportfish and aquaculture species, its obligate and opportunistic pathogens are well-studied compared to non-intensively cultured species. Yet its virome remains poorly understood. So far, we know of six viruses that infect largemouth bass.

Of these, Micropterus nigricans adomavirus 1 (MnA-1) causes blotchy bass syndrome, which shows up as hyperpigmented melanistic skin lesions. To better understand this disease, the study “Hiding in Plain Sight: Genomic Characterisation of a Novel Nackednavirus and Evidence of Diverse Adomaviruses in a Hyperpigmented Lesion of a Largemouth Bass (Micropterus nigricans)” collected symptomatic animals from Little Hunting Creek, USA, and sampled their lesions.

They identified Micropterus nigricans nackednavirus 1 (MnNDV-1) and three adomaviruses, with MnA-2 and MnA-3 previously unknown. The dsDNA MnNDV-1 is made of 3 kbp, with ORF1 encoding the core protein and ORF2 the viral DNA polymerase and reverse transcriptase.

In comparison, MnA-2 is made of 18 kbp with five unknown ORFs. For MnA-3, the scientists did not sequence the complete genome but found three ORFs, two of which were homologous to other adomaviruses. In summary, this study identified a new viral co-infection with three adomaviruses and one nackednavirus; yet, their association with the bass lesions remains unclear.

Grapevine viruses risking wine production

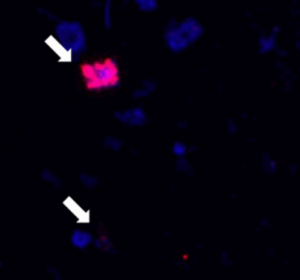

So far, scientists have described over 100 viruses that infect grapevines, with some of them causing diseases or productivity loss. In a vineyard in Canyon County, USA, grapevine leaves of symptomatic trees were sampled and enriched for viral genomic content.

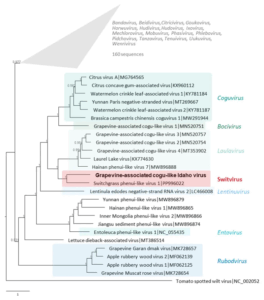

In the study “A Novel Cogu-like Virus Identified in Wine Grapes“, the researchers identified grapevine-associated cogu-like Idaho virus. Made of three single-stranded RNA segments, it is related to cogu- and cogu-like viruses of the Phenuiviridae family.

Each segment spans a single ORF encoding protein with homology to an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, a movement protein of cogu-like viruses, and a nucleocapsid. The genome segments and proteins are most similar to switchgrass phenui-like virus 1, with which the identified virus forms the new genus “Switvirus”.

Its impact on plant health, disease outcome, transmissibility, and morphology remains unknown. However, the study notes that Phenuiviridae generally produce enveloped spherical or pleiomorphic virions with a diameter of 80–120 nm and filamentous nucleocapsids inside.

Welcome to the new viruses in 2025

These newly discovered viruses from 2025 highlight the fascinating diversity of viral life across different domains and environments. From hypersaline solar salterns harbouring archaeal haloviruses to the potential therapeutic phages from cockroach guts, each study deepens our understanding of viral evolution and ecology. As sequencing technologies advance and sampling efforts reach unexplored niches, the viral landscape continues to unfold—revealing both pathogens and promising tools for biotechnology and medicine.

Missed the first blog of the New Microbes Discovered in 2025 series? Read New bacteria identified in 2025

Dr Sarah Wettstadt is a microbiologist-turned science writer and communicator writing for professional associations, life science organisations and researchers from the biological sciences. She runs the blog BacterialWorld to share the diverse and colourful activities of microbes and bacteria, based on which she co-published the colouring book “Coloured Bacteria from A to Z“. As science communication manager for the Scientific Panel on Responsible Plant Nutrition and blog post commissioner for the FEMSmicroBlog, Sarah writes about microbiology and environmental topics for various audiences. To help scientists improve their science communication skills, she co-founded SciComm Society. Prior to her science communication career, Sarah completed a PhD at Imperial College London, UK, and a postdoc at the CSIC in Granada, Spain. In her non-scicomm time, she enjoys playing beach volleyball on the sunny beaches in Spain or travelling the world.

About this blog section

Each year, the #NewMicrobes series for the #FEMSmicroBlog explores new species discovered throughout the year. Through several posts, we highlight the microbial diversity across all kingdoms by showcasing newly identified bacteria, viruses, fungi, and archaea.

| Do you want to be a guest contributor? |

| The #FEMSmicroBlog welcomes external bloggers, writers and SciComm enthusiasts. Get in touch if you want to share your idea for a blog entry with us! |