We have finally arrived at the last edition of the “New Microbes Discovered in 2025” series. It has been incredibly interesting to explore all these new viruses, bacteria, and fungi uncovered this year. In this last #FEMSmicroBlog of 2025, Sarah Wettstadt turns the spotlight on the archaea identified this year. As expected, the list is short, as research on this kingdom is limited. Yet, their metabolic capabilities are even more remarkable! #NewMicrobes

- Haven’t read the other editions of our new microbes series yet? Read about new bacteria identified in 2025, new viruses discovered in 2025, and exploring new fungi from 2025.

Archaeal extremophiles from acidic hot springs

Extremophiles are fascinating, as they thrive in conditions well outside the ranges that we consider normal. For example, the archaeal phylum Thermoproteota currently harbours species with optimal growth temperatures well above 55 °C.

The study “Polysaccharide-degrading archaea dominate acidic hot springs: genomic and cultivation insights into a novel Thermoproteota lineage” identified the two species Tardisphaera miroshnichenkoae and Tardisphaera saccharovorans in geothermal water and sediments from a mud spring in Kamchatka in Russia. These two are so different from currently known archaea that they were not only categorised into a new family—Tardisphaeraceae—but also a new order—Tardisphaerales—and even a new class—Tardisphaeria—within the Thermoproteota phylum.

The two thermoacidophiles grew solely in anaerobic medium supplemented with sulphur and at a pH 3.9–4.2. Tardisphaera miroshnichenkoae grows at 47 °C–70 °C, with an optimum of 55 °C–60 °C, and Tardisphaera saccharovorans at 37 °C–75 °C, with an optimum of 65 °C.

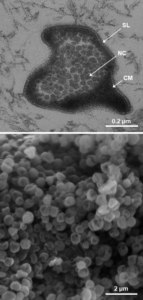

Both cells form small irregular cocci of 0.4–1.0 μm in diameter, are surrounded by a thick S-layer, and contain single pili-like appendages 10–12 nm in length. Both strains encode K⁺-uptake systems, whilst other potassium transporters or antiporters were not found, raising the question of how they would export cellular protons within these acidic environments.

Maritime ammonia-oxidising archaea

Ammonia-oxidising archaea are widely distributed across many environments, highlighting their ecological significance. During the oxidation process, they convert NH4+ to NO2−, which they directly use for cell growth and growth regulation.

The study “Nitrosarchaeum haohaiensis sp. Nov. CL1T: Isolation and Characterisation of a Novel Ammonia‐Oxidising Archaeon From Aquatic Environments” made use of an archaeal hotspot in Yangshan Harbour in the East China Sea. Here, they collected water samples to study the local archaeal community.

After 3.5 years of serial subculturing and dilutions, they obtained a culture with robust ammonia-oxidation capacity. They isolated Nitrosarchaeum haohaiensis, with the name derived from “Haohai”, translating to “ocean” in Chinese.

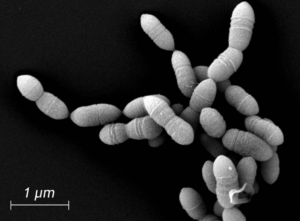

The short rod‐shaped archaeon was 1.2–1.4 μm in length and 0.5–0.7 μm in width, without pili or appendages. It oxidised ammonia most efficiently within a pH range of 7–8, a temperature range of 20 °C–25 °C, and a salinity of 2%–3%.

Whilst the morphology and size were consistent with closely related species, this member of the Nitrosarchaeum genus is the first one likely to produce extracellular vesicles. Even though their functions are still unclear, this discovery highlights the ecological importance of ammonia-oxidising microbes in marine environments.

Haloarchaea like it hot, red, and salty

In solar salterns, microbial diversity is dominated by halophilic microorganisms, with Halorubrum and Haloquadratum being the dominant genera. The genus Halorubrum is the largest one within the class Halobacteria, comprising 39 extremely halophilic species.

To shed light on haloarchaea, the study “Halorubrum miltondacostae sp. nov., a potential polyhydroxyalkanoate producer isolated from an inland solar saltern in Rio Maior, Portugal” analysed water samples from one hypersaline environment in Europe.

The researchers isolated 163 extreme halophiles, of which 129 were members of the Archaea domain. Of these, 125 belonged to the genus Halorubrum, with two strains clustering into a new species. The novel Halorubrum miltondacostae has the highest similarity to Halorubrum californiense and Halorubrum salinarum, and requires a minimal NaCl concentration of 10% to grow.

Its colonies were red-pigmented on medium containing 25% NaCl since the cells produce bacterioruberin and β-carotene. The researchers further confirmed the biosynthetic gene clusters for these pigments in the archaeon’s genome.

With optical microscopy, they showed polyhydroxyalkanoate granules surrounded by a layer of embedded synthetic and (de)polymerising proteins. However, the genes encoding these proteins were missing from the genomes, steering the way for future research to better understand this novel haloarchaeon.

Methanogenic archaea from human faeces

Even though often overlooked, the human gut microbiome also harbours various archaeal players. Methane-producing archaea from the genus Methanobrevibacter are especially abundant and interact with both host and non-archaeal cells.

From faecal samples from a human volunteer, scientists isolated a new methane producer, as described in the study “Expanding the cultivable human archaeome: Methanobrevibacter intestini sp. nov. and strain Methanobrevibacter smithii GRAZ-2 from human faeces“. The obligate aerobe Methanobrevibacter intestini grew optimally at 35 °C–39 °C and at a pH of 6.5–7.5.

Similar to other Methanobrevibacter species, it forms short rod cells with rounded ends and no pili or appendages. Some cells appeared fluffy on their surface, although it is not yet clear under which conditions it would produce this phenotype.

Since its growth depended on the presence of acetate, it might be involved in breaking down small fermentation by-products like other gut Methanobrevibacter species. Yet its metabolic abilities and ecological functions within the human gut microbiome need to be further investigated.

Welcome to the new archaea discovered in 2025

The archaeal species discovered in 2025 showcase the remarkable diversity and adaptability of this often-overlooked domain of life. From acidic hot springs, marine environments, to the human gut, this last edition of the “New Microbes in 2025” series reminded us of the metabolic capabilities and ecological roles of archaea. With better cultivation techniques, new environments will hopefully be explored to unravel more fascinating archaeal discoveries.

- Missed the other blog posts of this year’s New Microbes series? Read about new bacteria identified in 2025, new viruses discovered in 2025, and exploring new fungi from 2025.

Dr Sarah Wettstadt is a microbiologist-turned science writer and communicator writing for professional associations, life science organisations and researchers from the biological sciences. She runs the blog BacterialWorld to share the diverse and colourful activities of microbes and bacteria, based on which she co-published the colouring book “Coloured Bacteria from A to Z“. As science communication manager for the Scientific Panel on Responsible Plant Nutrition and blog post commissioner for the FEMSmicroBlog, Sarah writes about microbiology and environmental topics for various audiences. To help scientists improve their science communication skills, she co-founded SciComm Society. Prior to her science communication career, Sarah completed a PhD at Imperial College London, UK, and a postdoc at the CSIC in Granada, Spain. In her non-scicomm time, she enjoys playing beach volleyball on the sunny beaches in Spain or travelling the world.

About this blog section

Each year, the #NewMicrobes series for the #FEMSmicroBlog explores new species discovered throughout the year. Through several posts, we highlight the microbial diversity across all kingdoms by showcasing newly identified bacteria, viruses, fungi, and archaea.

| Do you want to be a guest contributor? |

| The #FEMSmicroBlog welcomes external bloggers, writers and SciComm enthusiasts. Get in touch if you want to share your idea for a blog entry with us! |