#FEMSmicroBlog: The gut microbiome of an ancient and almost extinct reptile from New Zealand

No animal is going it alone in this world. We all rely on our gut microbes to help us digest food and protect us from pathogens. Tuatara, an endemic reptile to New Zealand and the only living species in an otherwise extinct order, is no exception. The study “Limited gut bacterial response of tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus) to dietary manipulation and captivity” in FEMS Microbiology Ecology aimed to shed light on this reptile’s gut microbiome to learn more about how they interact with their environment, as explained by Carmen Hoffbeck. #FascinatingMicrobes

Tuatara – an ancient and evolutionarily distinct reptile

The tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus) is an omnivorous reptile endemic to New Zealand, where it has lived for over 200 million years. Once residing throughout the North and South Islands of New Zealand, human colonization and introduced predators like rats extinguished its mainland population in the 1800s.

Surviving populations exist only on predator-free offshore islands, in fenced mainland sanctuaries, or in captivity for their conservation. Within these centers, the goal is to better understand the animals and their dynamics over time.

To link the bacteria living in the tuatara gut to health outcomes, the study “Limited gut bacterial response of tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus) to dietary manipulation and captivity” in FEMS Microbiology Ecology analyzed gut microbial samples from tuatara living in three different captivity institutions. Tuatara at each institution were fed a single dietary item for four weeks, with their stools sampled one week before, four weeks during and one and two months after starting the diet.

About the gut microbiome of tuatara

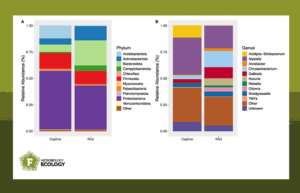

A previous study, the first on the microbiome of wild tuatara, showed that tuatara have a rather unique gut community among reptiles. Some of the most common bacteria seen in other reptiles, like Salmonella and Bacteroides, are virtually absent in the tuatara gut.

When looking at tuatara communities in sanctuaries across New Zealand, tuatara shared an unexpectedly large number of bacteria between individuals. This was even the case among individuals that live in sanctuary communities hundreds of kilometers apart.

It seems that the tuatara gut may be robust to disruption, while the study aimed to better understand the impact of dietary shifts on their gut microbiomes. Comparing captive tuatara to tuatara that spend less time in contact with humans will also elucidate what the “natural” gut bacterial community may look like.

The impact of diet on tuatara’s gut microbiome

Tuatara were fed a diet of field crickets, which usually make up a third or less of their diet. This mimics the shift in dietary availability tuatara would experience when they enter captivity and have less access to various invertebrates and plants. Even undergoing such a dietary manipulation, tuatara were robust to changes in their gut community.

Individual tuatara had some shifts in the relative abundance of their bacteria over the four-week experiment and in the following two months. Yet, bacterial richness was consistent over time with a core community of Alysiella, Gallicola, Chryseobacterium, Kingella, Neisseria, Luteimonas, and Snodgrassella. These were largely also present in wild tuatara in the same region.

During dietary manipulation, some bacteria, such as the notoriously underrepresented Bacteroides, were significantly more common in the tuatara gut while all core community members significantly decreased. However, all of these core members increased again throughout two months after manipulation.

There was no link between changes in the diet and changes in tuatara body condition. While the gut may have been slightly shifted, it had no immediate adverse effects on tuatara health.

Together, this study found that the tuatara gut appears to be remarkably stable in the face of disturbance, whether caused by a shift in diet or in living conditions. These results help understand how tuatara react to changes in the environment and diet and how they compare to other reptiles and to populations in the wild. Lastly, the study shed light on how this unique animal interacts with the world around us and how it might have survived for millions of years.

- Read the article “Limited gut bacterial response of tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus) to dietary manipulation and captivity” by Hoffbeck et al. in FEMS Microbiology Ecology (2024).

Carmen Hoffbeck is a PhD candidate at University of Auckland in New Zealand. She investigates host-microbe interactions, currently in the gut of tuatara – an endemic reptile to New Zealand – in the lab of Prof. Mike Taylor. During her bachlor’s degree at Linfield University she studied marine-microbe interactions in sponges, clams, and bryozoans. She received her master’s in biology at California State University Northridge where she studied ecology-evolution feedbacks between microbes and their plant hosts. She enjoys every part of biology, from working with animals in the field right up to computer modeling.

About this blog section

The section #FascinatingMicrobes for the #FEMSmicroBlog explains the science behind a paper and highlights the significance and broader context of a recent finding. One of the main goals is to share the fascinating spectrum of microbes across all fields of microbiology.

| Do you want to be a guest contributor? |

| The #FEMSmicroBlog welcomes external bloggers, writers and SciComm enthusiasts. Get in touch if you want to share your idea for a blog entry with us! |