Nine out of ten beers drunk worldwide are lager beers, and yet the yeast responsible for its fermentation is still a bit of a mystery. The lager yeast (Saccharomyces pastorianus) is a hybrid between two ‘parents’: the baker’s yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae and the elusive Saccharomyces eubayanus, very recently discovered in Europe for the very first time. But when and where did this hybridisation happen? The paper by Hutzler et al. “A new hypothesis for the origin of the lager yeast Saccharomyces pastorianus” in FEMS Yeast Research presents convincing evidence that the event took place at the court brewery (Hofbräuhaus) of Maximilian the Great, elector of Bavaria, in Munich in 1602. The hybridisation likely took place when the top-fermenting yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae inadvertently entered a bottom-fermenting culture of Saccharomyces eubayanus, Mathias Hutzler explains for the #FEMSmicroBlog. #FascinatingMicrobes

***Download the PRESS RELEASE on this link***

***This blog entry has been translated into German, Spanish, and Czech (links below)***

Historians have a hard job figuring out what happened when. The job might be even more arduous when yeasts, and not (only) people, are the main subject of a study. And even more so for the case when the estimated origin of that yeast is over 400 years ago, as it is the case with the lager yeast Saccharomyces pastorianus.

A rich culture of beer brewing

All it takes to brew beer is nothing more than grain, hops, water, and yeast. In practice, historical events played a crucial role in shaping recipes and production methods of the beers people drink today, as the paper “A new hypothesis for the origin of the lager yeast Saccharomyces pastorianus” in FEMS Yeast Research illustrates. A rich diversity in beer emerged.

The history of beer brewing also shaped yeast itself. Different brewing techniques selected for different yeast strains. Human intervention (like isolation, storage, and exchange of yeasts, as well as its inoculation from one batch to another), rulers’ ordinances (like the Bavarian ‘Purity Law’ of 1516 defining ingredients, brewing conditions, storage, and selling price), and serendipity played a role in the Saccharomyces pastorianus story.

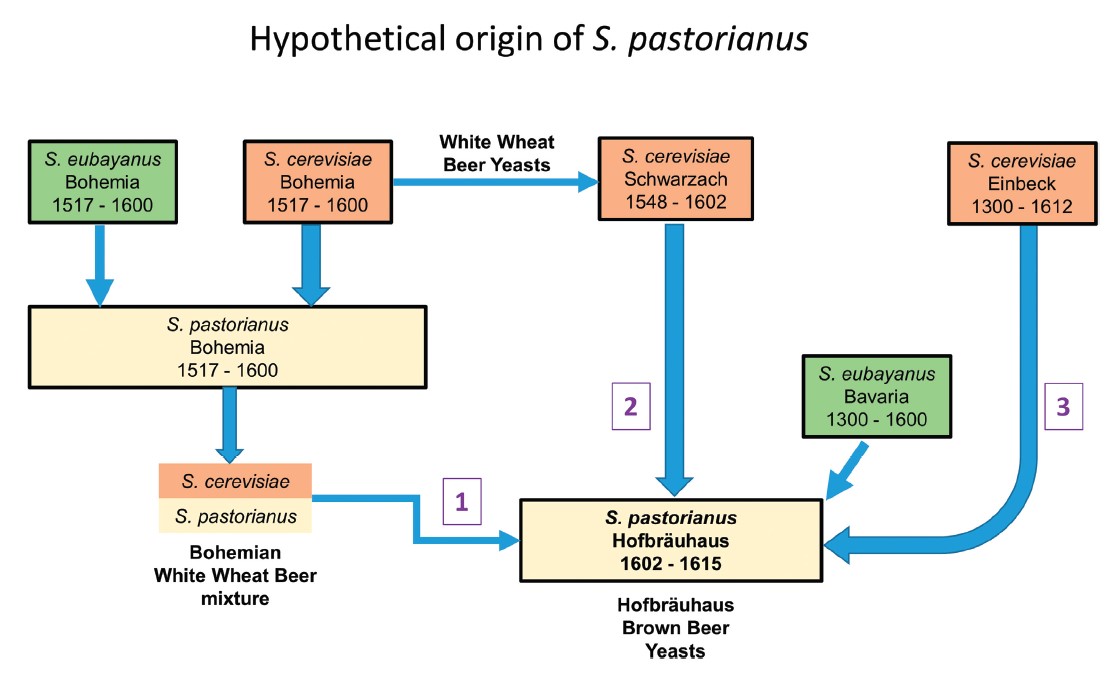

Serendipity is responsible for the emergence of the lager yeast Saccharomyces pastorianus after a hybridization between the top-fermenting yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae and the bottom-fermenting yeast Saccharomyces eubayanus. The authors formulating a new hypothesis for the origin of Saccharomyces pastorianus used historical records and contemporary phylogenomics to infer the events leading to the emergence of the lager yeast.

Culture in a beer glass

The study presents three main observations relevant to the origin and global distribution of the lager yeast, now responsible for 90% of all beer produced worldwide.

First: Bottom-fermentation was well-established before the Bavarian ‘Purity Law’ of 1516, allowing only bottom fermentation with barley, hops, and water for the brewing of ‘lager-style’ beer. However, excellent wheat beer made by top fermentation with Saccharomyces cerevisiae dominated production in neighbouring Bohemia. To limit the economic damage caused by Bohemian wheat beer imports, in 1548 the Bavarian ruler Wilhelm IV gave Baron Hans VI von Degenberg a special privilege to brew and sell wheat beer in the border regions to Bohemia.

Second: In 1602, the grandson of Hans von Degenberg died without an heir, and the new Bavarian ruler, Maximilian the Great, seized the special wheat beer privilege himself and took over the breweries once belonging to the von Degenberg family. In October of that year, the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae from the wheat brewery was brought to the Duke’s court brewery in Munich, where beer was brewed with a mixture of bottom-fermenting yeasts that the authors propose included Saccharomyces eubayanus. Thus, for a period of time, the brewery alternated with top- and bottom-fermentation in the same fermentation vessels. The study on the origin of the lager yeast proposes that this was the time and place of the famous hybridisation between Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Saccharomyces eubayanus and the lager yeast Saccharomyces pastorianus was born. This new hypothesis is contrary to the general assumption that Saccharomyces eubayanus was the contaminant that entered a brewery with fermentation dominated by Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Finally, the study shows how the Munich lager strains came to be the most successful yeasts for beer fermentation.

There is a certain irony the inability of Hans VIII von Degenberg to produce a son triggered the events that led to the creation of lager yeast. As one lineage died out, another began. No heir – but what a legacy Hans VIII left for the world!”—John Morrissey, co-author of “A new hypothesis for the origin of the lager yeast Saccharomyces pastorianus” in FEMS Yeast Research

Just the beginning

The hybridisation event that gave birth to Saccharomyces pastorianus was just the beginning. How is it possible that a strain born over 400 years ago is still extremely relevant today, despite the history of most beers being brewed and consumed locally until very recently?

The technologically advanced brewing methods and the willingness of Munich brewers to share their knowledge certainly played a role in the establishment of the lager yeast. Graduates who came to Munich to study the methods didn’t go away with just knowledge: they brought with them yeast strains too. The fact that Saccharomyces pastorianus does not thrive in natural environments and relies on human propagation for longer-term survival, was actually an asset for the yeast.

Then, from 1883 onwards, brewers started using pure cultures. Conservation, shipment and isolations of yeasts became crucial. Two major players were Emil Christian Hansen (1842-1909) in Copenhagen, who developed isolation of pure yeast by streaking, and Paul Lindner (1861-1945) in Berlin, who developed isolation by the droplet method using a microscope. Industrial processes, standardisation, and commercial interests played a role, too.

Max Delbrück objected to Hansen’s methods as late as 1887 based on the reasoning that mixtures of yeasts with different properties were more suited to imparting distinct flavours.” —from “A new hypothesis for the origin of the lager yeast Saccharomyces pastorianus” in FEMS Yeast Research

From 1900, brewers stopped giving away strains for free. Today, strains are coveted, and culture collections are economical attractive. Brewers and researchers are interested again in wild strains of yeast. There is certainly a lot of untapped diversity to uncover out there. In 400 years, will the worlds larger yeasts still be descended from Hans VIII’s original brew, or will a newer hybrid of perhaps undiscovered strains have taken its place in our humble beer glass?

- Read the study “A new hypothesis for the origin of the lager yeast Saccharomyces pastorianus” in FEMS Yeast Research by Hutzler et al. (2023)

- Download the press release

- Read also: #FEMSmicroBlog: Searching for the missing parent of the lager yeast in Europe

Mathias Hutzler was born in 1978 in Regensburg (Germany) and studied Food Technology and Biotechnology at the Technical University Munich (TUM, Germany). In 2009 he obtianed the Ph.D. at the Chair for Brewing Technology II, Technical University Munich. From 2009 he worked as division manager of the accredited laboratory for brewing/beverage microbiology and the yeast center of the Research Center Weihenstephan for Beer and Food Quality (Germany), and from 2013-2019 he was associate lecturer at the Department of Brewing Science, TU Berlin (Germany). In 2021 he obtained the Habilitation at the Faculty III Process Sciences, TU Berlin (Germany). Since 2022 he is Vice Director of TUM Research Center Weihenstephan for Brewing and Food Quality. Research focus: brewing microbiology, yeast technology, alternative fermentations, starter cultures, historic brewing technology, archeo-fermentation.

About this blog section

The section #FascinatingMicrobes for the #FEMSmicroBlog explains the science behind a paper and highlights the significance and broader context of a recent finding. One of the main goals is to share the fascinating spectrum of microbes across all fields of microbiology.

| Do you want to be a guest contributor? |

| The #FEMSmicroBlog welcomes external bloggers, writers and SciComm enthusiasts. Get in touch if you want to share your idea for a blog entry with us! |

This blog entry has been translated into:

- Spanish: #FEMSmicroBlog: ¿De dónde viene la levadura lager? by Alejandro Tejada

- German: #FEMSmicroBlog: Woher kommt die Lagerbier-Hefe? by Carolin Kobras (@carokobras)

- Czech: #FEMSmicroBlog: Odkud pocházejí ležácké kvasinky? by Vojtěch Tláskal